Krys Blackwood works for NASA designing the future of mission operations. She began her career in Silicon Valley working as both a researcher and designer before moving to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). She spoke to us about her upcoming projects, the skills required to do her job well, and overcoming gender bias in a male-dominated industry.

Tell us about your career path.

I spent about 20 years in Silicon Valley working in everything from Fortune 500 companies to tiny startups. I actually started as a web designer and web developer and I found that what I was really interested in was the interactive parts of the website.

Before I came to NASA JPL, I was a part of a team who were trying to make health insurance easier to get and help people to get the most out of their insurance. It felt really amazing to be doing something that was so altruistic. I felt like I was using my powers for good.

Ever since I was a little girl, I wanted to be an astronaut but that was not happening. I was applying to NASA as a UX designer for ten years so when the right opportunity finally opened up, I leapt at it! Here, I hope to save the whole planet by doing research that’s benefiting all of mankind.

What does a typical day look like at NASA JPL?

Every single day is different. And that’s probably one of my favourite things about my job.

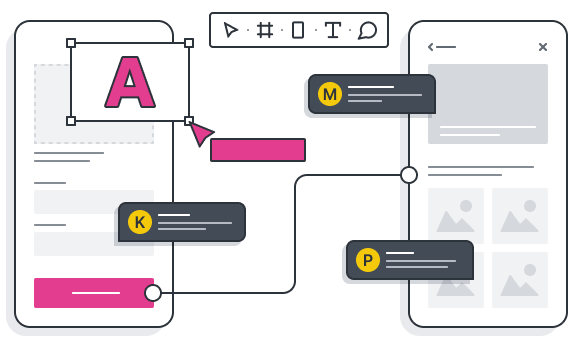

My day might consist of: project meetings, storyboarding panels for a day, working in Figma, designing a UI, observing scientists as they work, or interviewing subject matter experts. I’m not an astrobiologist so I need to lean on their expertise to find out exactly what automated missions need.

What are you currently working on?

Right now, I’m working on three projects. I work on the Europa Clipper project, where I’m helping to design the processes. It’s basically service design, service blueprinting and experience design for how we will run the mission once we’ve launched.

I’m also working on Europa Lander project where I’m helping to design the same things, but it’s in an earlier phase. Europa Lander is just a concept right now. I’m helping to create how we’re going to run the mission in advance. In May, we’re running a simulation activity where we’re actually going to prototype this mission long before we have a spacecraft.

I’m also doing research on human-autonomy teaming (how humans and autonomous agents work together to achieve a goal) for the Deep Space Network, which is an infrastructure project of antennas around the world. This is how we get back pictures from space and send commands to the spacecraft. I create the UIs for the operators to control those giant antennas and point them at the spacecraft and get data back. We’ve just released new software for them to use which only happens once every five to ten years so it’s pretty exciting!

Who do you work with?

In my section of JPL, there are 300 people focused on software. JPL is pretty big, there’s 5,000 people overall. When I am designing a new system or building a prototype, I’ll often be paired with UI and back-end developers. Sometimes I’ll be paired with back end-developers and I’m the one building the UI.

The most fun for me is when I’m prototyping an operations workflow. I’m working with people like rover drivers, astrobiologists, astronomers, and geologists who are working on the mission. We do a lot of role playing exercises to prototype an experience like that. It’s just a blast!

What do the role play exercises look like?

It can be anything from a few of us in a room with a paper prototype to 120 people altogether. In the Europa Lander project in May, there will probably be about 25 people online.

You literally pretend to be on the mission, even though you don’t have a spacecraft yet. It takes five years to build a spacecraft. We don’t wait until that’s done before we figure out whether these are the right processes.

When I was working in Silicon Valley, I could have an idea on Friday, and the release could be live on the site by Monday. I’d A/B test it and I’d have significant statistics by the following Friday. This is not so much the case at JPL where projects can take between one year and 15.

What skills do you need to do your job?

I would say there are three critical skills for my particular job.

The first is that I’m both a researcher and a designer. It’s really important that I can do the research to inform my designs myself, that’s a critical skill.

The second is being able to explain your decisions. Designers work with non-designers. It’s bad UX for your own design process if you come in and say “you have to do it because I’m the designer.” You need to be explain the process clearly to your stakeholders.

The third skill is resilience. Every designer runs up against that kind of critic who thinks they can do their job better. At JPL, they’ve been doing things a certain way for 84 years now and they’re really good at it. They’ve made voyages out past the edge of the solar system and they made them without us. So when we come in suggesting changes to established processes, the response can initially be quite sceptical. You have to learn not to take that personally.

What’s the biggest challenge of your role?

Getting a seat at the table at an engineering-focused organisation that has not traditionally embraced UX. It’s a lot of work to earn their respect and the right to contribute to a concept rather than dressing it up at the end.

We’ve come a long way though. JPL has had designers for seven years, I’ve been here for five and I’ve seen immense growth. I think that the constant public relations that designers have to do to earn that seat and the constant transparency is really good for us, but it’s also probably the hardest part of our job. Because when you’re busy sharing your methods, you’re not doing the work.

Have you ever experienced gender discrimination in your career?

I have worked at places where diversity in gender, sexual orientation, ethnic and cultural background were really embraced. However, I have experienced gender bias too.

There have been times when I was told I was too aggressive. There have been times when I was told that maybe I pushed things too hard and I would look around and feel I wasn’t pushing any harder than the men.

There were a lot of times where I was the only woman in a company. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they were discriminating against me, but it means that they weren’t emphasising diversity in their hiring practices.

My gender certainly didn’t stop my career; it stopped my growth at certain places, but then I just went to a different place.

At JPL, I will say I am delighted that my team is 50% female and many of the teams I work on have female leaders. Europa Clipper and Europa Lander both have female leadership and at least a 50% representation both in science and in engineering. And it’s really nice to be somewhere that it’s clear gender is not an issue.

How do you see your career changing over the next couple of years?

It’s hard to imagine better than what I’m doing now. I really love the variety of work and where I’m doing it. I am really excited about doing a tonne of research in the human autonomy teaming space.

I think that is possibly one of the directions that I want to chase is making the automation work better for the people, making sure that it’s a positive thing for mankind. And I hope that I can continue doing that at NASA for the rest of my life, because I think this is a place where my heart is so happy.

What advice would you give to those hoping to break into the UX?

Do an internship if you can to gain some real-world experience. That will really stand to you as a practitioner.

Another piece of advice is to take one project and do it for free for a charity. I’m a big believer in getting paid for your work, but it’s okay to do one project for free when you’re building your portfolio.

The third thing I always say is to keep applying even if you don’t get the job the first time. I’m living proof that if you keep trying, eventually you wear them down and they let you in.

Is there anything that you wish you knew about the industry before you started?

I wish that I had gotten proper training because the scaffolding that people get now is so much better and it sets them up with a common language and a structure for success.

Also, I wish that somebody had told me from day one how important it is to do public relations for yourself, particularly for women and people of colour.

You really have to shout from the mountain tops about the good work you’ve done because nobody else will do it for you. There’s also an expectation that if you’re not promoting yourself, you’re not doing good work. It’s not right but it’s the truth.